Microfoods for Caudate Larvae

By Jennifer Macke

Microworms

Microworms (nematodes) are approximately 0.5 - 2 mm (1/32 - 1/8") in length and extemely thin. They are suitable as food for only the smallest larvae, and only for the first few weeks of larval life. Anecdotal evidence suggests that larvae fed a diet of mostly microworms for too long do not grow well. Thus, microworms serve only as a "bridge" to larger foods. The advantages of microworms are that they are very easy to culture and cost very little.

The following is the way I culture microworms. Other instructions can easily be found on the Internet.

In a microwavable bowl, mix 1/4 cup quick oatmeal, 1/4 cup corn meal and enough water to cover them well (about 3/4 cup). Cover with a lid or plate and microwave for about 1.5 minutes. Let the mixture cool for an hour or more, undisturbed. Sprinkle with some dry yeast and mix. The mixture may be very stiff and hardened. That's OK. Add a little more water to help mix in the yeast. It's OK if it is still very lumpy. Put the mixture into a 16-oz plastic yogurt container or a deli cup with high sides. Add a little bit of starter culture. Put on the lid, but punch a few small air holes. Keep at room temperature. Start a new culture every 1-4 weeks, depending on whether you are using them, or just maintaining them for future use. (If you aren't using them, you won't mind the culture getting rather "old" before starting a new one.) Microworms are ready to harvest when they start to climb the sides of the container. Scrape them off with a toothpick, or something similar.

Brine shrimp (Artemia, "BBS")

The brine shrimp you need for small larvae are NOT the ones sold alive and swimming at pet stores. Those are adult brine shrimp, which are a suitable food for adult newts and very large newt larvae. We are talking here about freshly-hatched baby brine shrimp (sometimes referred to as "BBS"). These are approximately 1 mm (1/16") in size. They are fairly easy to hatch out from dry eggs (cysts), which can be purchased at pet shops or online.

To hatch out brine shrimp, you will need: brine shrimp eggs (or "hatch mix"), non-iodized salt, rock salt, or aquarium salt (not needed if you use hatch mix), and a hatchery device. Many instructions can be found for hatching artemia (see links below). Briefly, here is the procedure I have used. I have made my own hatchery, as shown below. I put into the hatchery:

2 cups (500 ml) tap or bottled water (chlorine is OK, but chloramine and dechlorinating drops are not OK)

1/8 - 1/4 teaspoon brine shrimp eggs

0.5 Tablespoon non-iodized table salt or aquarium salt

1/16 teaspoon baking soda (optional, if your water is acidic or soft)

This mixture is bubbled gently at room temperature, and shrimp are ready to begin harvesting in 2-3 days, depending on temperature. Some instructions for brine shrimp will insist that you need a strong light and warm temperature to hatch them. This is not true, in my experience. I routinely hatch them in 3 days at 65°F (18°C) without special lighting.

I use two hatcheries, with the batches staggered so that I have a constant supply. To harvest, I clamp off the airline tubing, let it sit for 1 minute, then I use a basting bulb to take out some of the liquid from the bottom and put it through a brine shrimp net. The empty shells of the brine shrimp float, and this part should be left behind. (NOTE: larvae will die if they injest the unhatched or empty shells of the brine shrimp!) If you don't have a brine shrimp net, you can use a kitchen strainer lined with a piece of fabric or nylon hosiery. Be sure to rinse thoroughly with fresh water, as you do not want to add salt to your aquarium.

Brine shrimp nets are sold in most pet shops. |

Axolotl larva after eating a meal of freshly-hatched brine shrimp. |

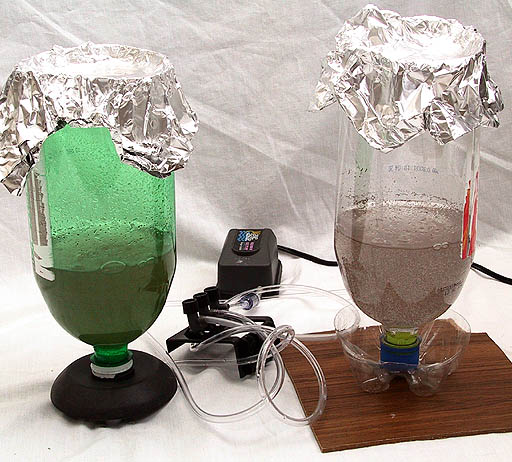

I made a hatchery as follows:

- Cut the bottom 2-3 inches (5-8 cm) off a 2-liter soda jug.

- Using aquarium sealant, glue a 3-foot (1-meter) section of aquarium tubing into the jug at the cap end. Alternatively, the tubing can be held in place by a cork or a 1-foot length of rigid tubing. The tubing will extend from the pump, in through cut-open end, down to the cap end.

- Using silicone sealant or epoxy, glue the jug cap onto a piece of thin wood. Almost any flat substance would work here, it just has to keep the thing from falling over.

- After curing, screw together the two parts, hook it up to a pump, and add hatching ingredients. Use aluminum foil (or the cut-off part of the jug, inverted) as a lid over the open end. It should bubble steadily, but not hard.

I am able to run two hatcheries from one pump using a gang valve. I use small binder clips to shut off the air when I am ready to take out some shrimp. With two hatcheries going, I can have a constant supply of shrimp.

Homemade brine shrimp hatchery. |

Two hatcheries attached to a small air pump. The hatchery on the left is sold in the US by San Francisco Brand. |

Daphnia & moina

Daphnia, or water fleas, are small aquatic crustaceans. Daphnia are ideal for newt larvae because they are freshwater organisms and survive in the tank until they are eaten. The commonly cultured varieties most useful for feeding newt hatchlings are Moina and Daphnia pulex. Moina are very small, similar in size to newly hatched brine shrimp. D. pulex is somewhat larger; full-grown D. pulex may even be too big for the smallest newt larvae.

One source for Daphnia is healthy pond water. If you skim a healthy pond with a small brine shrimp net, you are likely to catch many Daphnia and other small swimming creatures that newt larvae will eat. However, there are some risks in this method. You could introduce some undesirable germs or parasites from the pond. And you may catch some carnivorous insect larvae that could eat your newt larvae.

Daphnia can also be cultured with a minimum of equipment. Culturing Daphnia requires the following:

- a starter culture (from a pond or commercial source)

- a tub holding several gallons

- a source of algae ("green water"), either cultured, harvested outside, or bought as a concentrate (yeast, soy flour, and powdered spirulina can also be used)

- a source of coarse bubbles (unnecessary if raising them outdoors)

- a source of light (either sunshine or a plant light)

For detailed instructions for culturing Daphnia, there is an excellent Daphnia article at Caudata.org. Starter cultures of various kinds of Daphnia are available from many biological supply houses, and a few links are provided below.

Although Daphnia is an ideal food for newt larvae, culturing Daphnia is more complicated than hatching brine shrimp. It takes about two weeks to go from a starter culture to harvest. Another drawback to culturing Daphnia is that the culture tends to boom and crash. Even with careful monitoring and harvesting, my culture still had crashes. I raise Daphnia in a plastic tub holding about 5 gallons (20 liters). It has a lamp borrowed from one of my aquariums (15/20 gallon size). The lamp stays lit 24 hours/day. The airstone is modified to have large holes so that it produces large bubbles. Fine bubbles are supposed be bad for Daphnia.

Daphnia tub. Photo, Jennifer Macke, 2001 |

Daphnia magna, greatly magnified. |

Live whiteworms and Grindle worms

Whiteworms are easy to culture. An active culture produces worms of all sizes, so they can be used to feed larvae, juveniles, and even adults of a wide range of sizes. Grindle worms are similar, but smaller. The worms stay alive in water for a several days. Culturing instructions can be found on many sites on the Internet.

Evidence suggests that these worms lack the pigments (carotenoids) that allow development of orange colors in newts. Thus, they should not make up the majority of the diet for long periods.

Whiteworm culture. Photo, Jennifer Macke, 2004.

Live blackworms

Live blackworms are an ideal food for caudate larvae. Many larvae that hatch at a good size, such as Cynops species, can begin eating finely-chopped live blackworm from the beginning. Chopped pieces of blackworm will continue to wiggle and look alive for hours or even days. When the larvae get big, they are able to eat whole live blackworms. Many larvae have been raised on a diet entirely of blackworms, from hatching to metamorphosis. Health and growth rates of animals raised on blackworms are excellent. Blackworms are available at many good pet stores in the U.S., and by mail.

Image used by permission, aquaticfoods.com.

Live tubifex and other aquatic worms

Tubifex worms are an excellent live food that has been cultured for years by aquarists. However, they are uncommon in the U.S. because they are a bit difficult to culture. They are still available at some pet shops in Europe and Asia. Dried or frozen tubifex worms are available, but these usually contaminate tank water very easily and are not recommended.

A variety of miniature tubifex worm is now widely available, going by various names (Dero worms, microfex, small aquatic red worms). These worms are easy to culture and excellent food for newt larvae. However, it takes a month or more to get a culture going to the point that it is ready to harvest.

The following is the procedure I use to culture miniature tubifex.

Place the starter culture into a quart-size jar filled about 2/3rds full with aquarium water. Keep some kind of very loose lid on top to reduce evaporation, but still allow some air in. Feed with some kind of sinking food (one trout pellet, or a few "newt bites", or a tiny piece of raw fish, for example). Feed this amount approximately twice per week, increasing the amount slightly as there are more worms. You do not need to do any water changes. If the water evaporates below the half-way point, add a bit more aquarium water. When there are a lot more worms than there were to start with, transfer some to another jar and start it the same way. Always keep 3 or 4 jars going at once. When a jar gets old, it will crash (suddenly all the worms will die). When one jar crashes, just clean the jar and start it over again the same way. When you want to feed the worms to newt larvae, use an eyedropper or basting bulb to take some out into a clean container. Rinse a couple of times with clean water and feed. These worms should double their number every week or so. At first, this will seem like very slow growth. It will take a couple of months to get enough worms to start using them as food. But once you get them going, they are easy to care for and always there.

Other cultured microorganisms

There are other aquatic microorganisms that might be good food sources for newt larvae: scuds, cypris, cyclops, vinegar eels, and some of the larger infusoria. These are also available as starter cultures, but I have not tried them.

Bloodworms

Live bloodworms are an excellent food for larger larvae. Live bloodworms are available at only a few places in the U.S., but are more widely available in the U.K. and other countries. Some people have reported success raising larvae with chopped frozen bloodworms. With any non-live food, one must be more careful than ever to prevent mold and contamination of the water from decay.

Pond water method

by Joel Smith

"As soon as I noticed eggs, I set up another tank with gravel and water about 4 inches deep. Then I immediately went to a secret location that has a healthy pond full of aquatic bugs (copepods, daphnia, scuds and other stuff). I then take 2 - 3 large zip-lock baggies of pond water from the pond. Before I leave I run one of those fine baby brine shrimp nets through the pond over and over again to catch as many bugs as possible. These get dumped into the baggies of pond water. The goal of this is to get as much pond life as possible, without introducing large carnivorous bugs. It is easy to identify a healthy pond by the bugs in it. Usually I am able to see all kinds of stuff in the pond water before I leave. If you can't find a pond, I have found that floating aquatic plants from good nurseries often come with large amounts of daphnia, scuds and hydra.I then dump the baggies directly into the new hatchery tank. One thing to watch out for is large carnivorous insects in the aquatic phase. These are easy to identify once the stuff is dumped in the new tank. If you find any of these, they should be removed and maybe fed to larger newts.

I did this about one and a half weeks ago. The samples I got that time didn't have as many bugs as usual. I dumped it in the tank anyway and now my tank is full of life. I have copepods and daphnia all over the place, and hydra on the sides of the glass. There are probably lots of microscopic organisms also, but I haven't looked under a microscope.

It took my eggs (C. pyrrhogaster) about 20 days to hatch last time, and since the tank was full of life, I didn't feed the newts anything until they were large enough to eat tubifex worms, which was several months down the road. I place my tanks next to the window and put a few dollars worth of healthy cheap live seaweed-type plants in the water. I'm not using a pump, light, or oxygenator. Light comes from the window, oxygen is available due to the shallow water and aquatic plants. The only thing I have seen my newly hatched newts eat is copepods. Copepods will sit on a piece of gravel (eating algae I guess), and the newts will sneak up and grab them.

The biggest virtue of this method is that it is zero maintenance."

When using pond water, avoid dragonfly larvae, like this one.

These predatory insects eat amphibian larvae.

Pellet food method

by Meesa

"I know a lot of people recommend (and swear by) live daphnia cultures, or pond water skimmed for bug larvae. When my newts (Japanese firebellies) laid eggs, I didn't find them until it was too late to cultivate daphnia, so I had to find a quick alternative. (Plus, frankly, the cultures or pond skimming seemed, well, rather time-intensive - not that I wouldn't do it for my newts, but I thought there had to be an easier way...). The 'pellet mash' worked great for me. I used 'HBH' brand 'Newt and Salamander Bites soft sinking pellet diet.' I smooshed the pellets into a bowl containing a bit of warm water, and poured the liquidy gruel into the tank. I was pleasantly surprised by the positive results - I could see the newtlings 'jumping' up to get the small flecks.

I also recommend adding a few snails into the nursery tank to help clean it - I used just an airstone at first, until the newtlings got large enough to withstand an undergravel filter, and the snails really helped keep the tank free of leftover crud."

Further Reading

- Live food culture articles at SimplyDiscus. Includes instructions for microworms, whiteworms, moina, etc.

https://www.simplydiscus.com/library/foods_nutritions/livefood_cultures/index.shtml - Archives of live food discussions at the Krib. Includes extensive anecdotal information about brine shrimp, Daphnia, and many other live foods.

https://www.thekrib.com/Food/ - Daphnia article at Caudata.org.

https://www.caudata.org/resources/daphnia-an-aquarists-guide.6/

© 2001, Jennifer Macke. Article updated September 2004.