| Taricha torosa | |||||||||||

| California Newt | |||||||||||

| Taricha sierrae | |||||||||||

| Sierra Newt | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Taricha sierrae |

Taxonomy

In 2007, Taricha sierrae became officially recognized as a distinct species. Previously it had been a subspecies of T. torosa. The nominate subspecies, T. t. torosa, was formerly known by the common name "Coast Range Newt". At the time this information sheet was written, they were still subspecies.

Description

The California newt, T. torosa, is a relatively large caudate that can grow up to 20 cm (~8 inches). It is appropriately named "torosa," Latin for muscular or fleshy. Like all species of Taricha, it has a warty brown dorsal side and a yellow-orange ventral side. In outward appearance, T. torosa is very similar to T. granulosa. Traits specific to T. torosa include: 1) eyes that extend beyond the profile of the head, and 2) a yellow/light colored lower portion of the eyelid. The definitive way to differentiate T. torosa from T. granulosa is the pattern of the vomerine teeth on the upper jaw (see diagram below). T. torosa has a Y-shaped pattern, as compared to a V-shaped pattern for T. granulosa. T. torosa also lay their eggs in clusters as compared to T. granulosa, which lay individual eggs.

T. torosa showing light lower eyelid. |

Taricha torosa have Y-shaped pattern of vomerine teeth. |

Natural Range and Habitat

T. Torosa exist exclusively on the west coast of the United States, in particular California, with the main range extending from Humbolt County to San Diego. Isolated populations in different regions of California have varying traits, which led to the naming of subspecies. T. t. torosa and T. t. sierrae are valid subspecies. Some people still accept T. t. klauberi as a subspecies, while others do not.

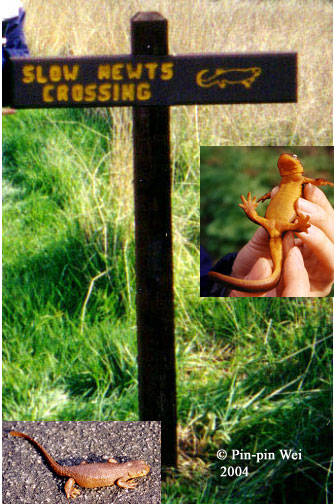

T. torosa are more terrestrial than T. granulosa, preferring to spend more time in forested and grassy regions. They are most visible from December to May when they migrate back to their breeding ponds. Often this involves crossing developed roads, and as a result, residents and local governments of California have closed sections of roads during the rainy season in order to protect the migrating newts. An excellent example is the closing of South Park drive in Tilden Regional Park between November and April in order to allow newts to safely return to their breeding ponds.

Due to their highly potent tetrodotoxin, California newts have relatively few predators other than man. The main natural native predator is the common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis). It is interesting to note that some garter snakes have developed a genetic resistance to tetrodotoxin, and these snakes tend to be slower than garter snakes without the genetic resistance (Brodie, 1999).

Some populations of T. torosa are threatened due to habitat destruction and the introduction of non-native predators such as mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) and crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) (Gamradt, S. C., Katz, L.B, 1996).

Captive Care

California newts are sometimes found in pet shops, except in California, where they are, ironically, illegal. However, they are often misidentified as "Oregon newts". This common name is a product of the pet trade, not even an officially-recognized common name, and it can refer to both Taricha granulosa and Taricha torosa. However, care for T. torosa differs significantly from T. granulosa in many ways, hence the importance of correctly identifying which species you have.

Both T. granulosa and T. torosa make an excellent beginning newt. Tarichas are known for their gregarious and relatively non-aggressive nature. California newts, like all members of the Taricha genus, contain tetrodotoxin, for which there is no antidote. It is essential to practice proper washing of hands and utensils which coming into contact with these newts.

T. sierrae. |

T. sierrae. |

Housing

Depending on which stage of life your T. torosa is in, a semi-aquatic or terrestrial set-up is required. See Setups Article in Caudata Culture for ideas on how to set up housing for your animal. The rule of thumb is two T. torosas for every 10 gallons (~38 L). Make sure the inhabitants of the tank are all about the same size, as T. torosa are opportunistic and enthusiastic eaters. A saying quoted from Wes von Papineau explains much of the behavior of this species:

- if it's smaller than you, eat it!

- if it's bigger than you, run away from it!

- if it's about the same size as you, mate with it!

Most California newts from metamorphosed juveniles to adults remain terrestrial except for mating. They have been found in relatively dry areas of southern California, so high humidity is not necessary. However, a shallow bowl of water in which the animal can fully submerge itself must be kept in the tank at all times, in case the local environment becomes too dry. Daily misting and absorbent substrates (moss, soil, sponge) are appreciated by this species, but it is by no means necessary to keep the terrarium dripping wet. Do not under any circumstances use shells, particularly the type which have a spiral hole. These are inviting dark places for newts, and you'll end up having to break the shell to retrieve your wayward newt.

Larvae of this species can be raised following this article: Raising Newts from Eggs. Right before the larvae metamorphose into juveniles, you need to move them to a secure tank or cover the current one. T. torosa are good climbers as soon as they emerge from the water, and will not hesitate to climb out of the tank (unfortunately to their deaths in our homes).

T. sierrae.

Feeding

Adult members of the Taricha genus, including T. Torosa, are second only to Pleurodeles waltl as the 'garbage cans of the newt world.' Their feeding habits are similar to T. granulosa, as they accept almost any kind of food. They appreciate live food in particular. They even eagerly accept Eisenia fetida, the redworm used for composting. The natural damp forested habitat of T. torosa is filled with slugs, worms, many insects, and other amphibians. You should vary the diet if you feel that one source does not provide all the nutrients necessary for survival. Captive raised members of this species have been fed exclusively on earthworms with no side effects.

My experience raising a T. t. torosa from egg to metamorph included these foods. Providing everything listed in the categories is unnecessary, unless you are experimenting with cultures that best suit your living environment and time commitment.

Stage: Food: Hatchling Baby brine shrimp (rinsed thoroughly). 1 week old Grindal worms/baby white worms

Baby brine shrimp

Small Daphnia2 weeks old Grindal worms

White worms

Daphnia

Chopped tubifex/blackworms3 weeks old White worms

Tubifex/blackworms

Daphnia4 weeks - metamorphosis White Worms

Adult brine shrimp

Tubifex/black worms

Gammarus

Earthworms

Breeding

Males often migrate and enter the pond first. Once T. torosa enter the water during the breeding season, they rarely leave. They undergo physiological changes during this aquatic phase. The female gets smoother skin and vertical broadening of the tail, allowing them to swim easily. Males develop extremely smooth skin (losing all granular texture), a broader tail, and nuptial pads on all four legs." These pads help them to clasp the females. Once the females arrive, mass mating ensues. These are not shy creatures! Often a dozen or so will mate within one cubic foot (~28 liters). During amplexus, which may last more than an hour, the male may stroke the female's cloaca with his hind feet and rub her snout with his submandibular gland. After amplexus, the male may deposit a spermatophore that the female may pick up with her cloaca. Females may mate with more than one male before laying eggs (Duellman, 1986).

The female lays egg masses that are protected by a toxic membrane containing the same tetrodoxin found in adults. The eggs of T. torosa are always laid in an egg mass of 7-30 eggs (Brame, 1968). If the egg cluster is not eaten as a tasty delicacy by one of the adult newts, the larvae hatch in 14-21 days. Within 3 months, most of the larvae metamorphose into juveniles of about 2 inches (~5 cm) or slightly longer. California newts, like many caudates, are able to live 12-15 years in the wild, sometimes longer in captivity with appropriate care.

Amplexus. |

During breeding, adults have smoother skin. |

The "mating ball" formed by mass amplexus. |

Female laying eggs. |

Egg mass. |

Embryo near hatching. |

Larva. |

Larva approaching metamorphosis. |

Juvenile T. torosa. |

Juvenile T. sierrae. |

Additional Resources

Deban, Stephen. 1996. "Autodax: Feeding in Taricha torosa"(video clip).

Berkeley Digital Library photos of Taricha torosa.

Berkeley Digital Library range map for Taricha torosa.

Acknowledgements

Uwe Gerlach and Nate Nelson edited and contributed much of their own insights, especially in the housing and breeding sections.

References

Brodie, E.D., Brodie, E.D., Jr., "The cost of exploiting poisonous prey: trade-offs in a predator-prey arms race." Evolution (1999) 53b: 626-631.

Brame, A. H., "The number of egg masses and eggs laid by the California newt, Taricha torosa." Journal of Herpetology (1968) 2: 169-170.

Duellman, W. E., and Trueb, L., Biology of Amphibians; 1986 The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Gamradt, S. C., Katz, L.B., "The effect of introduced crayfish and mosquitofish on California newts (Taricha torosa)" Conservation Biology (1996) 10: 1155-1162.

Petranka, J. W., Salamanders of the United States and Canada; 1998 Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C.

Riemer, W.J., "Variation and systematic relationship within the salamander genus Taricha." Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. (1958) 56: 301-390.

Twitty, V. C., "The species of Californian Triturus." Copeia (1942) 2: 65-82.

©2004 Pin-Pin Wei. Posted January 2004.